Fluvoxamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Faverin, Fevarin, Floxyfral, Dumyrox, Luvox |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682275 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 53% (90% confidence interval: 44–62%)[1] |

| Protein binding | 80%[1] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (via cytochrome P450 enzymes. Mostly via oxidative demethylation)[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 12–13 hours (single dose), 22 hours (repeated dosing)[1] |

| Excretion | Renal (98%; 94% as metabolites, 4% as unchanged drug)[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.476 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

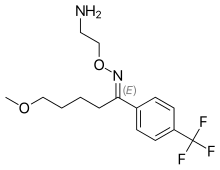

| Formula | C15H21F3N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 318.335 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| | |

Fluvoxamine, sold under the brand name Luvox among others, is a medication which is used primarily for the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),[3] and is also used to treat major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders such as panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.[4] Fluvoxamine CR (controlled release) is approved to treat social anxiety disorder.[5] It is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)[6] and σ1 receptor agonist.

The FDA has added a black box warning for this drug in reference to increased risks of suicidal thoughts and behavior in young adults and children.

Contents

[hide]Medical uses[edit]

Fluvoxamine's only FDA approved indication is in the treatment of OCD,[7] although in other countries (e.g. Australia,[8] the UK,[9] and Russia[10]) it also has indications for major depressive disorder. Fluvoxamine has been found to be useful in the treatment of major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders such as panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder, and other obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders. Fluvoxamine is indicated for children and adolescents with OCD.[11] The drug works long-term, and retains its therapeutic efficacy for at least a year.[12] It has also been found to possess some analgesic properties in line with other SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants.[13][14][15]

Some evidence shows fluvoxamine may be a helpful adjunct in the treatment of schizophrenia, improving the depressive, negative, and cognitive symptoms of the disorder.[16] Its actions at the sigma receptor may afford it a unique advantage among antidepressants in treating the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia.[17]

Adverse effects[edit]

Gastrointestinal side effects are more common in those receiving fluvoxamine than with other SSRIs.[18] Otherwise, fluvoxamine's side-effect profile is very similar to other SSRIs.[1][7][8][9][19][20]

- Common (1–10% incidence) adverse effects

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Weight loss

- Yawning

- Loss of Appetite

- Agitation

- Nervousness

- Anxiety

- Insomnia

- Somnolence

- Tremor

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Palpitations

- Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- Abdominal pain

- Dyspepsia (indigestion)

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Dry mouth

- Hyperhidrosis (excess sweating)

- Asthenia (weakness)

- Malaises

- Sexual dysfunction (including delayed ejaculation, erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, etc.)

- Uncommon (0.1–1% incidence) adverse effects

- Hallucination

- Confusional state

- Extrapyramidal side effects (e.g. dystonia, parkinsonism, tremor, etc.)

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions (e.g. oedema [buildup of fluid in the tissues], rash, pruritus)

- Arthralgia

- Rare (0.01–0.1% incidence) adverse effects

- Mania

- Seizures

- Abnormal hepatic (liver) function

- Photosensitivity (being abnormally sensitive to light)

- Galactorrhoea (expulsion of breast milk unrelated to pregnancy or breastfeeding)

- Unknown frequency adverse effects

- Hyperprolactinaemia (elevated plasma prolactin levels leading to galactorrhoea, amenorrhoea [cessation of menstrual cycles], etc.)

- Bone fractures

- Glaucoma

- Mydriasis

- Urinary incontinence

- Urinary retention

- Bed-wetting

- Serotonin syndrome — a potentially fatal condition characterised by abrupt onset muscle rigidity, hyperthermia (elevated body temperature), rhabdomyolysis, mental status changes (e.g. coma, hallucinations, agitation), etc.

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome — practically identical presentation to serotonin syndrome except with a more prolonged onset

- Akathisia — a sense of inner restlessness that presents itself with the inability to stay still

- Paraesthesia

- Dysgeusia

- Haemorrhage

- Withdrawal symptoms

- Weight changes

- Suicidal ideation and behaviour

- Violence towards others[21]

- Hyponatraemia

- Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Interactions[edit]

- CYP1A2 (strongly) which metabolizes agomelatine, amitriptyline, caffeine, clomipramine, clozapine, duloxetine, haloperidol, imipramine, phenacetin, tacrine, tamoxifen, theophylline, olanzapine, etc.

- CYP3A4 (weakly) which metabolizes alprazolam, aripiprazole, clozapine, haloperidol, quetiapine, ziprasidone, etc.

- CYP2D6 (weakly) which metabolizes aripiprazole, chlorpromazine, clozapine, codeine, fluoxetine, haloperidol, olanzapine, oxycodone, paroxetine, perphenazine, pethidine, risperidone, sertraline, thioridazine, zuclopenthixol, etc.

- CYP2C9 (moderately) which metabolizes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, phenytoin, sulfonylureas, etc.

- CYP2C19 (strongly) which metabolizes clonazepam, diazepam, phenytoin, etc.

- CYP2B6 (weakly) which metabolizes bupropion, cyclophosphamide, sertraline, tamoxifen, valproate, etc.

By so doing, fluvoxamine can increase serum concentration of the substrates of these enzymes.[22]

Fluvoxamine has been observed to increase serum concentrations of mirtazapine, which is mainly metabolized by CYP1A2, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4, by 3- to 4-fold in humans.[30]Caution and adjustment of dosage as necessary are warranted when combining fluvoxamine and mirtazapine.[30]

Pharmacology[edit]

| Site | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 11 |

| NET | 1,119 |

| 5-HT2C | 5,786 |

| α1-adrenergic | 1,288 |

| σ1 | 36 |

Fluvoxamine is a potent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with around 100-fold affinity for the serotonin transporter over the norepinephrine transporter.[23] It has negligible affinity for the dopamine transporter or any other site, with the sole exception of the σ1 receptor.[32] It behaves as a potent agonist at this receptor and has the highest affinity (36 nM) of any SSRI for doing so.[32] This may contribute to its antidepressant and anxiolytic effects and may also afford it some efficacy in treating the cognitive symptoms of depression.[17]

History[edit]

Fluvoxamine was developed by Kali-Duphar,[33] part of Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Belgium, now Abbott Laboratories, and introduced as Floxyfral in Switzerland and Solvay in West Germany in 1983.[33] It was approved by the FDA on 5 Dec, 1994 and introduced as Luvox in the US.[34] In India, it is available, among several other brands, as Uvox by Abbott.[35] It was one of the first SSRI antidepressants to be launched, and is prescribed in many countries to patients with major depression.[36] It was the first SSRI, a non-TCA drug, approved by the U.S. FDA specifically for the treatment of OCD.[37] At the end of 1995, more than ten million patients worldwide had been treated with fluvoxamine.[38]Fluvoxamine was the first SSRI to be registered for the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder in children by the FDA in 1997.[39] In Japan, fluvoxamine was the first SSRI to be approved for the treatment of depression in 1999[40] and was later in 2005 the first drug to be approved for the treatment of social anxiety disorder.[41] Fluvoxamine was the first SSRI approved for clinical use in the United Kingdom.[42]The largest manufacturer of fluvoxamine, drug substance, is Synthon BV (The Netherlands).

See also[edit]

- Clovoxamine, a chemically similar drug with a chlorine atom substituted for the CF3 substituent

- Caproxamine

- Demexiptiline, a tricyclic antidepressant with the same ketoxime termination chain as fluvoxamine

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f "PRODUCT INFORMATION LUVOX®". TGA eBusiness Services. Abbott Australasia Pty Ltd. 15 January 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Luvox". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "FDA Advisory Committee Recommends Luvox (Fluvoxamine) Tablets for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder," PRNewswire, 10/18/93

- ^ Karen J. McClellan, David P. Figgitt (Drugs October 2000). "Fluvoxamine. An Updated Review of its Use in the Management of Adults with Anxiety Disorders". Adis Drug Evaluation. 60 (4): 925–954. doi:10.2165/00003495-200060040-00006. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ Stahl, S. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: The Prescriber's Guide. Cambridge University Press. New York, NY. 2009. pp.215

- ^ Carlson, Neil R. (2013). Physiology of behavior (11th ed.). Boston: Pearson. p. 588. ISBN 0205239390.

- ^ a b "Fluvoxamine Maleate (fluvoxamine maleate) Tablet, Coated [Genpharm Inc.]". DailyMed. Genpharm Inc. October 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ a b Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ a b Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ "Summary of Full Prescribing Information: Fluvoxamine". Drug Registry of Russia (RLS) Drug Compendium (in Russian). Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ "US-FDA Fluvoxamine Product Insert". March 2005.

- ^ Wilde MI, Plosker GL, Benfield P (November 1993). "Fluvoxamine. An updated review of its pharmacology, and therapeutic use in depressive illness". Drugs. 46 (5): 895–924. doi:10.2165/00003495-199346050-00008. PMID 7507038.

- ^ Kwasucki, J; Stepień A; Maksymiuk G; Olbrych-Karpińska B (2002). "Evaluation of analgesic action of fluvoxamine compared with efficacy of imipramine and tramadol for treatment of sciatica—open trial". Wiadomości Lekarskie. 55 (1–2): 42–50. PMID 12043315.

- ^ Schreiber, S; Pick CG (August 2006). "From selective to highly selective SSRIs: A comparison of the antinociceptive properties of fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram and escitalopram". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 16 (6): 464–468. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.11.013. PMID 16413173.

- ^ Coquoz, D; Porchet HC; Dayer P (September 1993). "Central analgesic effects of desipramine, fluvoxamine, and moclobemide after single oral dosing: a study in healthy volunteers". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 54 (3): 339–344. doi:10.1038/clpt.1993.156. PMID 8375130.

- ^ Ritsner, MS (2013). Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I. Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. ISBN 9789400758056.

- ^ a b Hindmarch, I; Hashimoto, K (April 2010). "Cognition and depression: the effects of fluvoxamine, a sigma-1 receptor agonist, reconsidered". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 25 (3): 193–200. doi:10.1002/hup.1106. PMID 20373470.

- ^ Brayfield, A, ed. (13 August 2013). Fluoxetine Hydrochloride. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ Taylor, D; Paton, C; Shitij, K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ^ "Faverin 100 mg film-coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Abbott Healthcare Products Limited. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Top Ten Legal Drugs Linked to Violence". Time Inc. 7 January 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ a b Ciraulo, DA; Shader, RI (2011). Pharmacotherapy of Depression (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 49. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-435-7. ISBN 978-1-60327-435-7.

- ^ a b Brunton, L; Chabner, B; Knollman, B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ P., Baumann (1996). "Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship of the Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 31 (6): 444–469. doi:10.2165/00003088-199631060-00004. PMID 8968657.

- ^ Gill HS, DeVane CL; Gill, HS (1997). "Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Fluvoxamine: applications to dosage regime design". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (Suppl 5): 7–14. PMID 9184622.

- ^ DeVane, CL (1998). "Translational pharmacokinetics: current issues with newer antidepressants". Depression and Anxiety. 8 (Suppl 1): 64–70. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)8:1+<64::AID-DA10>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 9809216.

- ^ Bondy, Brigitta; Illja Spellmann (2007). "Pharmacogenetics of Antipsychotics: Useful For the Clinician?". Curr Opin Psychiatry. Medscape: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 20 (1): 126–130. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f69f. PMID 17278909. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Kroom, Lisa A. (10-01-2007). "Drug Interactions With Smoking". Am J Health-Syst Pharm. Medscape: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 64 (18): 1917–1921. doi:10.2146/ajhp060414. PMID 17823102. Retrieved 2008-01-31. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ^ Waknine, Yael (April 13, 2007). "Prescribers Warned of Tizanidine Drug Interactions". Medscape News. Medscape. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ a b Anttila, Sami AK; Rasanen, Ilpo; Leinonen, Esa VJ (2001). "Fluvoxamine Augmentation Increases Serum Mirtazapine Concentrations Three- to Fourfold". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 35: 1221–1223. doi:10.1345/aph.1A014. ISSN 1060-0280.

- ^ Owens, MJ; Knight, DL; Nemeroff, CB (1 September 2001). "Second-generation SSRIs: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine". Biological Psychiatry. 50 (5): 345–50. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01145-3. PMID 11543737.

- ^ a b Hashimoto, K (September 2009). "Sigma-1 receptors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical implications of their relationship". Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (3): 197–204. doi:10.2174/1871524910909030197. PMID 20021354.

- ^ a b Sittig's Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia (PDF) (3rd ed.). William Andrew. 2008. p. 1699. ISBN 978-0815515265. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ "Drugs.com―Fluvoxamine". Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ "Brand Index―Fluvoxamine India". Archived from the original on 2013-10-18. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Omori, IM; Watanabe N; Nakagawa A; Cipriani A; Barbui C; McGuire H; Churchill R; Furukawa TA (October 2013). "Fluvoxamine versus other anti-depressive agents for depression". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD006114. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006114.pub2. PMC 4171125

. PMID 20238342. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

. PMID 20238342. Retrieved 14 October 2013. - ^ "OCD Medication". Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 17 October2013.

- ^ Fluvoxamine Product Monograph. 1999. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Luvox Approved For Obsessive Compulsive Disorder in Children and Teens". http://www.pslgroup.com/dg/2261a.htm. External link in

|journal=(help) - ^ Higuchi, T; Briley, M (February 2007). "Japanese experience with milnacipran, the first serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor in Japan". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 3 (1): 41–58. doi:10.2147/nedt.2007.3.1.41. PMC 2654524

. PMID 19300537.

. PMID 19300537. - ^ "Solvay's Fluvoxamine maleate is first drug approved for the treatment of social anxiety disorder in Japan". http://www.solvaypress.com/pressreleases/0,,33713-2-83,00.htm.External link in

|journal=(help) - ^ Walker, R; Whittlesea, C, eds. (2007) [1994]. Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics (4th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-4293-5.